Clive Barker’s Hellraiser

October 26, 2010 3 Comments

A shirtless man is fondling a brass puzzle box whose idea of “No means no” involves spewing out flesh-piercing chains. The attic room he occupied fils with dangling hooks and spinning pillars adorned with flesh. The man, who we will soon learn goes by the name Frank Cotton, is reduced to a few gallons of blood soaking the woodwork, his face strewn about the room in chunks. Another man steps out of the dark. He is dressed in leather that stylishly draws attention to his various abdominal wounds. He is almost a silhoutte, but the light drifting down over the back of his hairless, ghost white flesh exposes a grid carved into his head, with a pin hammered into his skull at each intersecting line. He places the chunks of Frank’s mutilated face back together, in a jigsaw, and caresses the surface of the box. In a flash, all the chains and gore are gone, leaving the room as barren as if nobody was ever there.

Halfway through the film, we get an exposition dump from Frank (who, long story short, has been revived from blood spilled on the floor and must be fed even more blood in order to restore his nerves, skin and musculature) that he opened the box because he wanted to get laid. But not just any lay: a lay with greatness that transcends this boring, vanilla world. In a world before 4chan, a world of fluffy eighties hair, Frank has tired himself of every debauchery available to him, and has become disillusioned. He wants something sicker and freakier. To remedy this problem, he purchases a magic puzzle box from the most Asian man he can find and uses it to summon a cabal of priestly butchers/S&M freaks simply referred to as ‘the Cenobites’; who proceed to chain fuck him until he’s goo on the floor.

We get into the narrative swing of things when Frank’s brother Larry and his stuck up dick of a wife Julia move into the old Cotton childhood home. The place has been abandoned since their mother died, allowing Frank to be as indescreet in his perversions as a man can be. There’s maggots, roaches and rats crawling over food in the kitchen, gaudy statues of Jesus and the Virgin Mary adorned with Christmas lights, pictures of naked women and obscene art all scattered and thick with dust in damp, cluttered rooms. Frank is the bad boy of the family and Larry is the boring, goody-goody. Larry, poor boy, wants to settle down, renovate, start over–a prospect that alternatively bores and disgusts his wife, who gives off an impression of desperation; of being old and no longer desired, pining for the bygone days of her youth where she was stuffed with more cocks than a poultry farm. If this were a less blood-drenched drama, she’d be an infidelity waiting to happen, and she is in this one, too, but it’s overshadowed a bit by the fact she’s pining for the reanimated corpse of her husband’s brother.

In a flashback that makes the camera throb, they had the kind of torrid affair that can only be iniated by pulling out a switchblade and cutting off her dress. In the barren attic where Frank died, she clutches her hands over her heart and moans in ecstasy as she relives the eye fisting that he and only he could give her. This happened on the night before her marriage. On top of her wedding dress. I could once again remind you that this women is a dick, but in her mind, she is a victim, trapped by crusty societal norms, doomed to live out a life in a loveless marriage, too afraid to take the ridicule necessary in leaving a man for his infinitely more sexually potent brother. She cries. Is love alien to her? Like Frank, does she only live for the thrill of the moment? If so, has it never crossed her mind to try and spice things up with a new position or some toys? Maybe go to the library and check out a few bodice-rippers?

Though we will leave her later for Larry’s smokin’ hot daughter Kirsty, for the first half of the film, Julia will be our protagonist: an anti-heroine who kills to either relive a lost love she never got to fully reciprocate or work one more good fuck in her life before the onset of menopause. The script does a good enough job of distracting you from the fact that the killings are basically the hobby of a bored housewife that you almost believe the former.

In a scene that borders on the lyrical, Julia relives her rough fucking, with a torn photo of Frank pressed firmly against her bosom, while intercutting scenes of Larry and two movers lifting the massive marital mattress up a narrow flight of stairs. In a sort of visual pun, Larry gashes his hand on a rusty nail halfway jammed into the wall while his brother’s hard throbbing dick thrusts into his bethroed’s probably not so tight pussy. Demonstrating the kind of spinelessness that almost makes Julia’s contempt for him understandable, he crawls up the stairs into the attic, bleeding profusely, whining about how he doesn’t like blood and how he’s going to faint and throw up. Julia acts like an icy, cooing mother and they’re off to the hospital for stitches. An invisible force absorbs the spill into the space betwen the boards and nails. What follows is a marvelous display of practical effects: Frank’s rebirth. The floorboards shake. A postulate slime halfway between molasses and amniotic fluid seeps up through the floor. Frank’s skeleton pops out of the woodwork with the gusto of a broadway baby outta Liza Minelli’s cunt and proceeds to steadily grow: brain, muscles nerves. All the while Christopher Young’s beautifully Gothic score swells out in the background.

Though initially horrified, Julia’s disgust soon gives way to fascination, then arousal; as it often does when seeking out new porn. As fucking a skinless fetal zombie is beneath a dick of her breding, she primps and proves to herself that she still has the capacity to seduce balding English businessmen, who she beats to death with a hammer for the nutriment of her beloved. Pounding on a guy until liquid comes out is probably another visual pun, but we won’t dwell on that.

Barker explains he intended Hellraiser to be something different in regards to the run-of-the-mill slasher movie. He pointed out that the genre was dominated predominately by two archetypes: the lumbering, silent brutes like Michael Meyers and Jason Vorhees and the murderous stand-up comedians who spew out one-liners with the indiscrimiante glee of bills from broken cash machines, such as Freddy Kruger and Chucky. Barker wanted to do something different. He wanted a monster who could feel. A monster who could emote. In that regard, he succeeded. The true antagonists here are not the deadpan Cenobites–who basically get about ten minutes out of an hour and a half–but Frank and Julia. It’s obvious he doesn’t love her. Before becoming this parasitic, flesh-eating abomination, he was a pick-up artist; a predator of female vulnerability. But how could she possibly claim victimhood? It didn’t take much to push her to kill. She displays guilt, self-disgust and other trappings of human decency, but only briefly–just as fast as it comes, it feeds back into a controlling thrill. Just as Frank puts on more flesh with each victim, she cakes on the make-up and does up her wavy hair harder and harder.

While the house is quit large, how is it plausible that Larry could be dense enough to overlook the adulterous cannibal living in his attic? The original novel, The Hellbound Heart, mentions that Rory (as was his name in the book) wanted to give Julia space, so he decided to stay out of her special “damp” room. He probably thought the room was damp because Julia went up there for a bit of the ol’ fish n’ finger pie; and watching movie Julia’s overexerted gasping at the mere memory of Frank’s pulsating charisma, that guess can’t be too far off.

Larry’s afformentioned daughter Kirsty, who lives in an aprtment in town, and not her father’s decrepit mansion, is repelled by the acidic presence of Julia–who is definitely the kind of woman who makes passive-agression into an artform. In a subplot that goes nowhere, she meets a presumably British boy with offensively bad fashion sense and proceeds to get stalked by a cricket eating hobo that could give the Man behind Winkie’s a run for his money.

He’s “presumably” British, because there’s ambiguity as to whether or not this film takes place in the US or the UK. Listening to the film’s commentary track, even Mr. Barker shrugs his shoulders and basically tells you to decide for yourself. We see a very British train pass in the background, and then the obvious implication of Kirsty and her boyfriend’s dialogue is meant to imply he’s British. When discussing why Kirsty doesn’t like the clearly British Julia, she says “She’s just like you, so prim and proper!” to which her boyfriend replies, in a very stereotypically British voice, “I beg your pardon!” On the flipside, a lot of British actors were awkwardly dubbed over by less offensive American voices, including the main antagonist Frank, because in a film involving demons, sado-masochism, murder, bodily dismemberment, briefly glimpsed full-frontal male nudity, bare tits, exposed viscera and bug-eating, British accents were the only thing the producers thought wouldn’t fly in the puritanical US.

The film almost falls apart in the third act, at least in the realm of consistent narrative logic. Kirsty meets with her father in a Chinese restaurant as he thinks Julia is all alone at home, going stir-crazy, so he wants his daughter to go keep her company and try to make friends. She catches Frank and Julia in the act of murder-adultery and narrowly escapes with the puzzle box. Frank it seems, desperately wants to molest his niece, so throw “incest fantasies” on that list of transgressions in the last paragraph.

This was foreshadowed in Kirtsy’s dream: she’s in a room of floating pillow fluff, the liliting sound of a shrieking baby drifting some somewhere unknown, a blood-stained human form lying still under a white sheet. Then, boom, corpse-in-the-box. The body presumably belongs to her father, but it’s not easy to tell–dummy’s not very good. For some reason, Barker cuts to Kirsty’s boyfriend waking up scared, while Kirsty still lies in bed, fidgeting up telegraphed nightmare thrashes. I suppose Barker just wanted to screw with the audience, because obviously the boyfriend wasn’t having that dream. Why did Barker cut from a dream sequence to someone who wasn’t having the dream waking up? In fact, why is Kirsty having prophetic dreams about her father’s death? Is the implication that the boyfriend was supposed to be have the same dream? Are they sharing a psychic dream space or doing it in the dream sea Quiddity? Just as quickly as these answers are raised, they are forgotten as Kirsty calls her dad and Frank is bein’ chill, jus’ hangin’ out on the staircase above, whispering “Kirsty” the world practically drooling off his oily lips. And who can blame him? Not only is Julia a dick, but she’s like forty. That kind of baggage is strictly “hit it and quit it” material.

When Kirsty awakes in a hospital room, a nurse sitting nearby is watching the Blooming Flowers Network–the only station in America or the British Isles that offers 24/7 coverage of suggestive rose blooms (sadly, in the twenty years since this film was released, the’ve branched out into reality TV and pro-wrestling). This is clearly symbolic of adolescent sexual awakening, especialy when later juxtaposed with the flower-like shape of the opening puzzle box, but it’s the kind of symbolism with so little basis in what has henceforth been psuedo-reality that it raises a big fat “Why?” if you try to think about it logically. The film really hasn’t been surreal enough to seem to warrant a metaphorical reading up until now, but perhaps Kirsty has entered a fugue state as it’s going to take more and more breakdowns in logic to the point where it seems like that’s what it wants us to do. A doctor locks Kirsty in her room, with the puzzle box and says the police want to talk to her. Why? What did Kirsty do? Is this suddenly a Kafkaesque nightmare where she’s being persecuted for no reason? Or was it just because there was some blood on her shirt? There was blood on the box too, but it looks pretty clean now, so if your goal is preserving evidence, you’re pretty shit at it, doc.

With all the curiosity and glee of a prepubescent sexual awakening–rosebud, baby–Kirsty opens the box and you would expect her to be immediately skewered by chains like Frank, but that doesn’t happen. Instead, the wall opens up and leads into a stone corridor thick with cobwebs and the same cries of a screaming baby from her dream. She pauses as she sees a silhoutte in the darkness ahead. It hovers off the ground, long curving feet grasping the ceiling, shriveled clawed arms dangling below. Before Kirsty has time to process this, it moves into the light, and she gets chased by some kind of screaming scorpion fetus monster. The tension of the moment is delfated somewhat, because first of all, the thing is not a very convicning prop. Not only can you see the wheels behind it, but you can see the crew pushing. This could have been avoided with some creative editing or lighting on Barker’s part, but as it stands, it’s very sloppy filmmaking. Second of all, it’s delightful! A fetus with a stinger! This thing could abort itself! It’s every mother’s dream!

Kirsty, of course, narrowly escapes back into the hospital, whipping around fast enough to break a lesser woman’s neck to see that the corridor has vanished, but the wails and scratching of the monster are still audible behind the wall. Things move so quickly that we never have time to contemplate why Frank got chained the second he opened the box, but Kirsty gets to go to another dimension and see an incredibly suggestive looking monster. Nor do we ask why it is that somebody seems to have set the fog machine all the way up to “Silent Hill” so the Cenobites can individually teleport into the room with much fanfare and glowing squiggly lines. Not only do they not immediately chain fuck her, but they give her a convenient explanation of who they are and what they do. We are left to presume that Frank was not given the same courtesy because he’s a gross dude with a greasy porno stash and the Cenobites don’t swing that way. As the sequel will make abundantly clear, the Cenobites and their magic simply operate on narrative convenience.

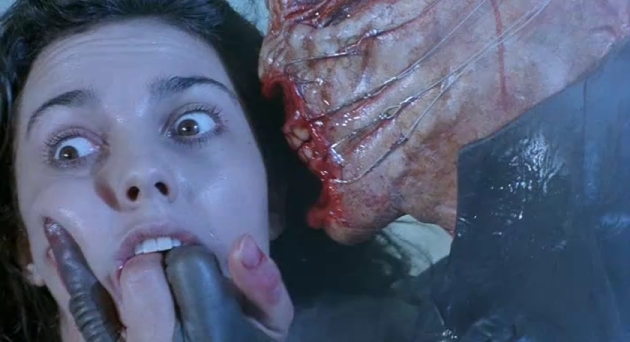

Kirsty, quick thinker that she is, strikes up a bargain with the leather demons, all while being fingered in the mouth by the most mutilated one. She’ll lead them to Frank, who “escaped” them if they promise not to chain fuck her. Kirsty, you see, is not into the kinky stuff. She’s kind of lame. That’s why she’s in a relationship with the most pointless character in the film. It might not make a whole lot of sense, but on the upside, the entire scene is beautiful shot and wonderfully atmospheric. The Cenobite makeup and designs are beautiful in their visceral unease. The Lead Cenobite, called “Pinhead” in the sequels due to his fondness for piercings, is in particular very enigmatic with a commanding presence. Watching this scene, it’s no wonder he eventually became a horror icon that not even the godawful second half of Hellraiser 3 could bury. The only other Cenobite to speak is the Female, who was originally called “Deepthroat” due to a gash in her neck pried apart by barbed wired that, um… hehehe. That’s cute.

When Kirsty returns home, she finds her father dead; skinned by Frank and Julia. It takes Kirtsy a few moments to realize this is the case because Frank is wearing Larry’s skin. Gotta give it to these two: they turned Kirsty’s huge dork of a father into what basically amounts to an incest gimp suit. Dissenting voices may wonder exactly how this works. The sensible mind knows draping someone else’s skin over your own will make you look like some awful, saggy blow-up doll and not like a real person. While you can read this breakdown of the family unity as a resulting of a Faustian pact metaphorically (though why anybody would want to be Larry, figuratively or literally is an enigma) the form-fitting skin routine has roots in the films internal logic. Frank is supernatural. Seems he sucked the skin onto his muscles somehow. He apparently has tiny suction cups on his fingers. Watch the film and you can see that he feeds on the blood of the flabby by jabbing his fingers into people’s necks (one such murder is even dubbed over with the sound of a straw sucking up the last drops of soda from the bottom of a bottle). It would appear, he acquired some kind of vacuum attachment for his fingers while he was dead, because most living people don’t have that. Oh, before we forget! Guess what Frank and Julia did the second Frank got new skin? If you answered “Baked fresh chocolate chip cookies”, then you’re an idiot, because the obvious answer is that they had more rough sex.

Sadly, their doomed romance is doomed to end as Frank stabs Julia, eats her blood and chases Kirsty until the Cenobites magically appear and chain fuck him a second time. For some reason, there’s what is obviously a giant pizza cutter cutting into Frank’s spine. There’s a sort of fairy-tail logic at work, as the Cenobites only appear after Frank says his name and confesses to his crimes. Kirtsy, still reeling from her father’s death, watches Frank’s head ripped open and strewn across the room and is immediately stalked by demons with eyes glistening with erotic desire. A lesser woman could curl into a ball of gibbering trauma, but Kirsty is far too spunky. So spunky in fact, that we never question why the Cenobites suddenly want to kill her. She upheld her end of the bargain, but I guess you just can’t trust pain worshipping kink demons to keep their word.

We also do not question why Julia is dead, on a blood-soaked mattress with the puzzle box in her hands, face mutilated beyond recognition. Frank killed her in the stairwell. Her presumably dead body must have gotten up, found the puzzle box, then crawled into bed with it. Why would her dead body do this? Who knows? This is Julia’s reward for being the most interesting character in the film and then unceremoniously thrown away in the last half-hour. Kirsty’s boyfriend and his awful shirt show up, and this raises the question of how Kirsty got out of the locked hospital room. You see, he was there, but she was already gone. Guess the Cenobites can unlock doors from the outside. While they were at it, they probably picked up Julia’s body, carried her to the bedroom and solved the box for her. All while rubbing their hands and twirling a bit of lacerated flesh like a curly mustache for completing their evil plan for setting up a sequel.

Kirsty furiously rubs on the brass-plated clitoral metaphor that controls the plot and discovers that she can send the Cenobites back to their dimension by returning the box to its original shape. Presumably, she could have tried this back at the hospital, but didn’t. The Cenobites, who have the power to chain fuck her at any time, decide not to, and just wait around while she fumbles with the box and sends them back. The box either displays some sort of sentience or it can be manipulated by forces from the other side, as the box alters its shape in a previously unseen way and from the darkness of her front door, the scorpion fetus puppet emerges and roars fearsomly at Kirsty. Though rather than tearing at her with his jaws and teeth, they get in a silly slap-fight. Oh, and the house is collapsing, presumably because it could no longer stand the sexual tension.

In the end, Kirsty and her boyfriend make it out alive. We see a photo of Frank, the same photo Julia took earlier, interlaid over the house and the photo burns; the obvious implication of which is that the house burns down. Of course, Mr. Barker is also unsure of whether or not this is true. Again, everything within the film implies this, but Barker doesn’t seem to believe it. The house is still standing in the sequel, and Barker states in the commentary that he probably didn’t intend for the house to burn down. Not only does the aforementioned interlay and fade imply the burning, but the film ends on the (admittedly very crappy) burnt ruins of the house. Okay, it’s not burnt ruins. It’s some flaming furniture in an empty field. One of the pieces of furniture is a chair seen in the attic, but why it survived, while the rest of the house didn’t, is anyone’s guess. If the house didn’t actually burn, then that just means Kirsty went walking until she found a field full of random burning furniture that somebody left out. Either way, this final sequence is damn silly.

When Kirsty tries to destroy the box through immolation, the random hobo who was chasing her manages to track her down and pick up the box. He burns up in the fire, but that’s all right, because his true form is that of a giant skeletal dragon demon who takes the box and flies back to Chinatown, so the overtly Asian man can sell it to some other disillusioned pervert. They apparently have a system worked out. The film ends before we can ask why the hobo dragon was following Kirtsy if his goal was to retrieve the box. Shouldn’t it have been staking out Frank’s house? In fact, for all it knows, Frank is still dead! Shouldn’t it have broken into the house, gone into the attic, taken the box and flied away? The only logical reason for following Kirsty around would be that it can see into the future, and thus it knew that Kirsty would have the box by the end of the movie. But that makes even less sense! If it knew Kirsty would eventually have the box, shouldn’t it also know that she got the box from Frank? Why not just go to Frank’s house, summon the Cenobites and keep balding British men off the endangered species list? Or maybe it did know that and just decided to take a vacation in the meantime. He no doubt said to himself “If I intervene now, I won’t be able to dick around this ambiguously British city for a few days and eat pet-shop crickets! Fuck it. This random hot chick will do my job for me. I’m gonna stare at her ominously, just for laughs.”

Thus ends Hellraiser. As far as the woefully underutilized slasher-melodrama-body horror hybrid genre goes, it’s a wonderfully engaging spectacle. The characters, though ripe for mockery, are memorable and the acting is only hilarious enough of the time to provide an occassionally dissonant chord to compliment the drama. The makeup and effects are stunning if you’re watching a bad VHS copy, transporting you into a latex nightmare of goo and blood that you will not soon forget. The direct sequel, Hellbound: Hellraiser II, makes even less sense, and somehow manages to be even juicier and more ridiculous, but it’s well worth watching, even if just for the camp value and inspired but poorly executed art-direction. Sadly, of the film’s seven (soon to be eight) sequels, it is the only one to use similar atmosphere and aesthetic cues. Once Hellriaser 3: Hell on Earth was shat out of the Hollywood sequel anus, the films lost something vital that was never again replicated.

I was google-image searching Julia for a scratchboard project I plan to start today, and accidentally stumbled on your “Hellraiser” review, which is spot-on and fucking hilarious. I have watched “Hellraiser” more times than I can count, but apparently my blinding love for Doug Bradley has blocked me from ever spotting the crew pushing the scorpion fetus monster. And all this time I had no idea they were supposed to be standing in the ashes of the burned down house at the end — I thought they were at the dump where the hobo dragon lived. Clearly I need to rewatch with your viewing guide beside me. But right now I’m going to peruse your review section, fingers crossed that you have addressed the offensively shitty wigs in “Bloodline.” Also this: “Toymaykuuuhhhhh…” Thanks for the laughs!

I’m thrilled you dug my little review. Hard to believe it’s almost four years old; didn’t think anyone would bother with the damn thing.

Sorry to let you down about Bloodlines. I did, ages ago, watch every flick in the series–including some of the latter sequels I hadn’t seen before–with the intent of reviewing them all, but Christ if I can remember why that never happened. Twenty-year-old me was a bit of a lazy prick.

Anyhoo, thank you again. There’s no feeling quite as delightful as logging into an old inbox to find something you’d almost forgot you’d written brought someone some joy.

So, this review is super old, but highly hilarious.